This story is part of our Weekend Reads series, where we highlight a story we love from the archives. It was originally published on June 22, 2020.

In the most iconic scene of The Devil Wears Prada[1], Andy (Anne Hathaway) nonchalantly dismisses two nearly identical blue belts in a room full of fashion forward elites. Andy’s icy, terrifying boss Miranda (Meryl Streep) retorts with a diatribe so full of vitriol that it effectively knocks Andy down a peg. It also illuminates Andy’s own naive contributions to the very stylistic machinery she so blithely critiques: Miranda traces the origins of Andy’s “lumpy blue sweater” all the way back to the explosion of the color cerulean in Oscar de la Renta and Yves Saint Laurent’s early 2000s runway shows, before filtering down to department stores and eventually discount retailers where Andy “no doubt, fished it out of some clearance bin.”

Miranda’s acerbic history lesson sets into motion Andy’s transition from frumpy intern to uber-glam fixer, but it also does a favor for anyone interested in visual culture.

The past offers a wellspring of formal, conceptual, and philosophical inspiration, making a deep knowledge of design history necessary for stylistic innovation. Knowing design history gives context to our contemporary visual culture—we can use the past to decode the present and forecast a stylistic future.

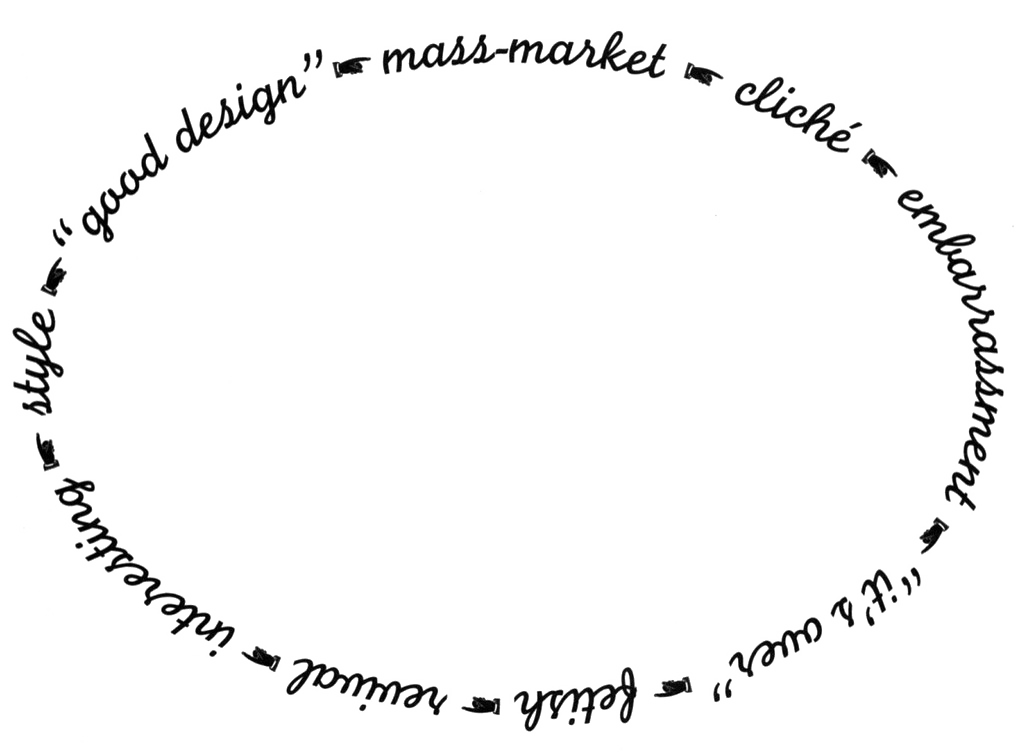

One of the best blueprints of this idea is Lorraine Wild’s “Great Wheel of Style[2],” which charts how style repeatedly drifts in and out of high and low culture like an undertow. In an interview for Eye Magazine in 2000, Wild suggests that style and a universally agreed upon notion of “good design” are intertwined: Good design creates intrigue and gets consumed by the mass market, which hijacks and superficially proliferates form devoid of its context. This results in cliché, embarrassment, then death, followed by fetishism, revival, and curiosity.

But what is good design other than a subjective and inherently flawed concept? When design and context are inextricably linked, it is good. When design detaches from its context, we are left with cliches, embarrassments…deaths. Wild’s Great Wheel of Style plays out as design oscillates from the intriguing to the unimaginative. It’s a helpful reminder for designers and design students today: if you borrow from a certain style, it’s important to know where that style came from, as well as the social and cultural contexts that gave that style its rise.

For a classic example of this style cycle, one needs to look no further than the Memphis Group[3]. In the 1970s, when Ettore Sottsass retreated from “Corporate Italy”— abandoning his position designing modular office space at Olivetti—he found himself in the eye of a perfect storm of modernist disruption. He resisted high paying commercial jobs in favor of collaborations with pioneering artists, architects, and critics, including SuperStudio and Archizoom. While reading a 1977 edition of the New Wave magazine WET, Sottsass encountered the outrageously garish designs of ceramicist Peter Shire, with whom he later fathered the Memphis Group, an artist collective where tastelessness prevailed. The group’s animated furniture and objects represented a clean break from Modernism, hurling them into the New Wave with brilliant, jewel tone color palettes adorning idiosyncratic geometries, new age kitsch, and functional impracticality.

Around the same time, graphic designers like April Greiman and Dan Friedman contributed their own stylistic improvisation, using technology and dark room experiments resulting in early Macintosh 8-bit aesthetics. Greiman’s designs from this period reflect her formal Swiss training coupled with Memphis-inspired, California New Age, flaunting explosive colors and garish oddities that played on anti-taste styles of the New Wave. Friedman, too, developed a self-bred mix of peculiarity and logic through a radically modern formalism.

Within a decade, the style had ballooned out of its sub-cultural roots and into the mass market, setting the 1980s aglow. Both David Bowie and Karl Lagerfield bought entire Memphis collections to furnish their respective New York and Paris apartments. The iconic forms became a sort of kit of parts, and soon every surface, interior, and textile was veneered in Memphis inspired aesthetics—think 1980s sitcom Saved by the Bell, or 1990s hit Pee Wee’s Playhouse. By the late ’80s, the style had gone from fad to cliché to generic, soon entering the lowest vernacular markets like airport gift shops where, in any hub across the country, you could find a white mug, with a 2” x 2” grid overlapping a pastel triangle, with Your City> written in Mistral script.

Per Wild’s wheel, the style had surpassed mass market to embody cliche and embarrassment. Fast forward twenty years, and a Memphis rebirth thrust it back into the public consciousness. Christian Dior fetishized the look in his 2011 runway show. Supreme released Memphis-inspired skateboard decks. Retail outlets like American Apparel regurgitated the iconic and kitschy geometry. Today, London-based graphic artist, Camille Walala[4], represents the logical endpoint to Memphis’s style evolution, elevating the work back into high culture with her refreshed Memphis-inspired interior design at high-end boutique Opening Ceremony in Tokyo.

Tracing the work of Walala—or Christian Dior, or even Supreme’s uninventive rip-offs for that matter—to its origin sheds light on the market’s influence on style and form. We all know that style goes from high to low and high again, but identifying a style’s context breeds visual literacy and shepherds innovation. And it’s not just necessary for aesthetic innovation, it’s also necessary for good design. We can only avoid Andy’s faux pas in The Devil Wears Prada when we consider context.

For another example, let’s turn to the 2009Want It campaign for Saks designed by Shepard Fairey’s Studio Number One, whose uncanny impersonation of Constructivism recycles more than just a visual language.

In the late 1910s and early 1920s, Constructivism grew out of a Soviet State sponsored movement designed to disseminate political doctrine. Collectivism, universality, practicality, industry, and purity evoked the new Soviet utopia, yielding a simplified red, black, and white Communist palette. Designs like El Lisstizky’s iconic Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge and layouts for Vladimir Mayakovsky’s For the Voice, featured intoxicating thick red and black stripes, primary shapes, and images that comprised a universal language engaging an illiterate peasant population. Type was meant to be seen and heard. The dynamically composed forms conjure a vision of the new world, “constructed” through a new visual architecture.

Unlike the Memphis Group, the Constructivist style cycle suffocated under Stalin’s 1930s Socialist Realist mandate, and thus never made it to the mainstream. It tip-toed around subsequent cliche, embarrassment, death, etc. on the Great Wheel of Style, yet over the decades, the style was still fetishized and revived. In one prominent example, Neville Brody’s 1980s design for The Face looks like a page out of Mayakosvky’s book, with heavily ruled type, directional marks and idiosyncratic typographic maneuvers that operate linguistically and graphically.

Yet whereas Brody’s design was less a wholesale rip-off of Constructivism, and more an homage to its anti-corporate and anti-establishment approach, Studio Number One’s advertising campaign for the luxury department store copied it verbatim. English language messages were written in geometric, Cyrillic-inspired letterforms to connote Russian typography. The campaign’s black and white photography mimics that of Alexander Rodchenko’s photos of spirited Communist youths gazing toward an idealized future.

At first glance, seeing a high-end retailer like Saks appropriate the Constructivist methodology to sell high fashion to their beau monde clientele was a complete assault on the original Soviet mission—it felt completely out of context. And indeed, fetishism and revival can be dangerous when it decontextualizes a style from its social or political origin. Yet upon closer examination, Want It theoretically stoked the 2008 recession-era economy. Studio Number One hijacked the Constructivist ethos to fire up a patriotic faith through unmitigated stylistic quotation. In many ways, Studio Number One outsmarted the market with a posture that lower forms of imitation failed to assume. Despite the nearly hundred years separating the Constructivist and Studio Number One campaigns, a repeat performance of art and politics converge, the context presented itself once again. Studio Number One consciously hopscotched the Great Wheel of Style, landing squarely back at the cradle of good design.

For designers who may feel like everything under the sun has already been done, the cycling of style contains a strange type of reassurance: it has been done, and it will be done again.

Understanding this underscores the importance of design history. Knowing your history nourishes originality and edifies creative disruption—a prerequisite for our contemporary postmodern, hyper-exposed and hyper-accessed context. The burden remains on us to translate the past to be good innovators.